Why did the Acadians leave France?

http://www.

History of Acadia

Acadia has its origins in the explorations of Giovanni da Verrazzano, an Italian explorer serving the king of France. In 1524-25 he explored the Atlantic coast of North America and gave the name "Archadia", or “Arcadia” in Italian, to a region near the present-day American state of Delaware.

1603

2015

History of the Name "Acadia"

Acadia has its origins in the explorations of Giovanni da Verrazzano, an Italian explorer serving the king of France. In 1524-25 he explored the Atlantic coast of North America and gave the name "Archadia", or “Arcadia” in Italian, to a region near the present-day American state of Delaware. In 1566, the cartographer Bolongnini Zaltieri gave a similar name, "Larcadia," to an area far to the northeast that was to become Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The 1524 notes of Portuguese explorer Estêvão Gomes also included Newfoundland as part of the area he called “Arcadie” (see also Acadia).

French Presence (1534--1713)

The abundance of cod off the coast of Newfoundland was known of long before the explorations of Jacques Cartier (see Norse voyages; Fisheries History). In 1534, during the first of three voyages to Canada, Cartier made contact with Mi’kmaqs in Chaleur Bay.

The first French colonists did not arrive, however, until 1604 under the leadership of Pierre du Gua de Monts and Samuel de Champlain. De Monts settled the 80-odd colonists at Île Sainte-Croix on the St Croix River. The winter of 1604–05 was disastrous, scurvy killing at least 36 men.

The next year the colony looked for a new site and chose Port-Royal. When some French merchants challenged his commercial monopoly, de Monts took everyone back to France in 1607; French colonists did not return until 1610. During this time the French formed alliances with the two main Aboriginal peoples of Acadia, the Mi’kmaqs and the Maliseet.

Factors other than commercial rivalry stifled Acadia's development. In 1613 Samuel Argall, an adventurer from Virginia, seized Acadia and chased out most of its settlers. In 1621 the government renamed Acadia Nova Scotia and moved in the Scottish settlers of Sir William Alexander (1629). France appointed Charles La Tour as lieutenant-general of Acadia in 1631, however, and he built strongholds at Cape Sable and at the mouth of the Saint John River (Fort La Tour, later Saint John). Alexander's project of Scottish expansion was cut short in 1632 by the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, which allowed France to regain Acadia.

Renewed Presence and Settlement

Renewed settlement took place under Governor Isaac de Razilly, who moved the capital from Port-Royal to La Hève, on the south shore of present-day Nova Scotia. He arrived in 1632, with "300 gentlemen of quality" (see Lahave). A sailor by trade, Razilly was more interested in sea-borne trade than in agriculture and this influenced his decision where to establish settlements. As early as 1613 French missionaries participated in the colonial venture. By the 1680s a few wooden churches with resident priests were established.

Razilly died in 1635, leaving Charles de Menou D'Aulnay and La Tour to quarrel over his succession. D'Aulnay moved the capital back to Port-Royal, then proceeded to wage civil war against La Tour, who was solidly established in the region. D'Aulnay was convinced that the colony's future lay in agricultural development that assured both self-sufficiency in food supply and a stable population. Before his death in 1650, D'Aulnay was responsible for the arrival of some 20 families. With the arrival of families, agricultural production was stabilized and adequate food and clothing became available.

French-English enmity once again affected Acadia's fate, causing it to pass to the English in 1654 and back to the French through the Treaty of Breda(1667). It was taken by the New England adventurer Sir William Phips in 1690 and returned to France again through the Treaty of Ryswick (1697).

Establishment of New Colonies

Starting in the 1670s, colonists left Port-Royal to found other centres, the most important being Beaubassin (Amherst, Nova Scotia) and Grand-Pré (now Grand Pre, Nova Scotia). The first official census, held in 1671, registered an Acadian population of more than 400 people, 200 of which lived in Port-Royal. In 1701 there were about 1400; in 1711, some 2500; in 1750, over 10 000; and in 1755, over 13 000 (Louisbourg excluded).

These highly self-reliant Acadians farmed and raised livestock on marsh lands drained by a technique of tide-adaptable barriers called aboiteaux, making dikeland agriculture possible. They hunted, fished and trapped as well; they even had commercial ties with the English colonists in America, usually against the wishes of the French authorities. Acadians considered themselves "neutrals" since Acadia had been transferred a few times between the French and the English. By not taking sides, they hoped to avoid military backlash.

Peninsular Acadia was not the only region with a French population along the Atlantic. In the 1660s, France established a fishing colony at its post Plaisance (now Placentia, Newfoundland). In both regions the French population appeared to enjoy a fairly high standard of living. Easy access to land and the absence of strict regulations allowed the Acadians to lead a relatively autonomous existence. A vital contribution to the survival of the Acadians was made by the Mi’kmaqs. At the end of the 17th century aboriginal peoples exerted considerable influence on the Acadians due to their knowledge of the woods and the land.

Into the Hands of the English

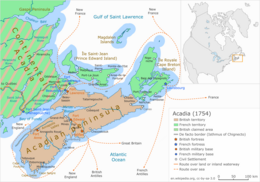

Following the War of Spanish Succession (1701-13), Acadia passed definitively into the hands of the English. Through the Treaty of Utrecht, Plaisance was ceded along with the territory which consisted of "Acadia according to its ancient boundaries," but France and England failed to agree on a definition of those boundaries. For the French, the territory included only the present peninsular Nova Scotia, but the English claimed, in addition, what is today New Brunswick, the Gaspé and Maine.

Difficult Neighbours (1713-63)

Following the loss of "Ancient Acadia", France concentrated on developing Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) and Île Royale (Cape Breton Island), two largely ignored regions until that time. On Île Royale, Louisbourg was chosen as the new capital. Louisbourg had three roles: a new fishing post to replace Plaisance; a strong military presence; and a centre for trade. Île St-Jean was more looked upon as the agricultural extension of Île Royale.

Even though the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht provided for the theoretical departure of the Acadians, they showed little initiative to move to the new French colonies because of the lack of marshes that were so vital to their agricultural system. As well, the British authorities at Port-Royal (renamed Annapolis Royal) did not facilitate the transfer but rather interfered in its process. They were worried about the emptying of the colony of its population and the subsequent increase in the population of Île Royale. Acadian farmers were also needed to provide subsistence for the garrison.

Except for the garrison at Port-Royal, the English made virtually no further attempt at colonization until 1749 in what was once again named Nova Scotia. From 1713 to 1744, the small English presence and a long peace allowed the Acadian population to grow at a pace which surpassed the average of this whole era. To some historians, it is considered Acadia's "Golden Age."

England demanded of its conquered subjects an oath of unconditional loyalty, but the Acadians agreed only to an oath of neutrality. Unable to impose the unconditional oath, Governor Richard Philipps in 1729–30 gave his verbal agreement to this semi-allegiance.

In 1745, during the War of the Austrian Succession, Louisbourg fell to an English expeditionary force whose land army was largely composed of New England colonists. However, France regained the fortress through the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748), to the great displeasure of the New England colonies. It was in this context that England decided to make the Nova Scotian territory "truly" British.

Deportation

In 1749 the capital was moved from Annapolis Royal to Halifax. Intended to serve as both a military and a commercial counterweight to Louisbourg, Halifax was selected because it was a better seaport and was far from the Acadian population centres. England finally took steps to bring its own settlers into the colony. They came primarily from England and from German territories with British connections (Hanover, Brunswick, etc). From 1750 to 1760, an estimated 7000 British colonists and 2400 Germans arrived to settle in Nova Scotia.

The French authorities reacted by building Fort Beausejour in 1751 (near Sackville, New Brunswick) to keep the English from crossing the Isthmus of Chignecto into their "new" Acadia. The British wanted to keep an eye on the French and their Mi’kmaq allies, and so constructed Fort Lawrence. They also wanted to protect potential English settlers and stop any possible invasion by land coming from Canada.

With Louisbourg and Canada in the north, Fort Beauséjour in the east and an Acadian population viewed as a potential rebellious threat, the British authorities in Halifax decided to settle the Acadian question once and for all: by refusing to pledge an unconditional oath of allegiance, the population risked deportation. The British first captured Fort Beauséjour and then again demanded an unconditional pledge of allegiance to England.

Caught between English threats and fear of French and aboriginal retaliation, Acadian representatives were summoned to appear before Governor Charles Lawrence. Taking the advice of Father Le Loutre, the representatives initially refused to make the pledge, but they ultimately decided to accept. In 1755, Lawrence, dissatisfied with an oath pledged with reluctance, executed the plans for deportation.

The Politico-Social Context of the Deportation

The deportation occurred as a result of the contemporary geopolitical situation and was not an individual choice made by Lawrence. He knew that English troops under General Braddock had just been bitterly defeated by French armed forces in the Ohio Valley (see Fort Duquesne). Fears of a combined attack by Louisbourg and Canada against Nova Scotia, theoretically joined by the Acadians and the Mi’kmaq, explains, to a certain degree, the order for deportation.

The deportation process, once instigated, lasted from 1755 to 1762. The settlers were put into ships and deported to English colonies along the eastern seaboard as far south as Georgia. Others managed to flee to French territory or to hide in the woods. It is estimated that three-quarters of the Acadian population were deported; the rest avoided this fate through flight. An unknown number of Acadians perished from hunger or disease; a few ships full of exiles sank on the high seas with their human cargo.

In 1756 the Seven Years' War broke out between France and England. The two French colonies, Île Royale and Île Saint-Jean, fell in 1758. Being French subjects, their settlers were expelled and repatriated to France. More than 3000 settlers were deported from Île Saint-Jean alone, half of them losing their lives by drowning or through disease. The Treaty of Paris(1763) definitively put an end to the French colonial presence in the Maritimes and in all of New France.

The Founding of a New Acadia (1763-1880)

After 1763 the Maritimes took on a decidedly English face when New England planters settled on lands earlier inhabited by the Acadians. English names replaced French or Mi’kmaq ones almost everywhere. The English at first reorganized the territory into a single province, Nova Scotia. In 1769, however, they detached the former Île Saint-Jean, which became a separate province under the name of Saint John's Island; it received its present name of Prince Edward Island in 1799. In 1784 present-day New Brunswick was in turn separated from Nova Scotia, following the arrival of American Loyalists who demanded their own colonial administration.

As for the Acadians, they began the long and painful process of resettling themselves in their native land. England gave them permission once they finally agreed to take the contentious oath of allegiance. Some returned from exile, but the resettlement was largely the work of fugitives who had escaped deportation and of the prisoners of Beauséjour, Pigiguit, Port-Royal and Halifax who were finally set free.

They headed for Cape Breton, where they established themselves along the coast by the Île Madame and on the island itself; for the southwest tip of the Nova Scotia peninsula and along St Mary's Bay; and to northwestern New Brunswick (Madawaska). A small number also established in Prince Edward Island, but the majority of Acadians went to the eastern parts of New Brunswick.

Economic Decline

The British authorities preferred to see the Acadians spread out over the territory and the Acadians themselves accommodated this directive, since it allowed them to avoid the regions with a British majority. British settlers then, in the majority of the cases, occupied the lands formerly owned by the Acadians.

Most Acadians, except for those on Prince Edward Island and in Madawaska, found themselves on less fertile land, and so these former farmers became fishermen or lumberers, cultivating their land only for subsistence. As fishermen, they were exploited and subjected to great dependence and poverty, especially by companies from the Isle of Jersey.

In 1746, the British Crown annihilated the Scottish Catholics in the Culloden massacre. The Protestant Crown stripped the Acadians of their civil and political rights because they too were Catholics; they could neither vote nor be members of the legislature. From 1758 to 1763, they could not even legally own land. Nova Scotian Acadians gained the right to vote in 1789; those in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island in 1810. After 1830 Acadians could sit in the legislatures of all three colonies following the enactment of the Roman Catholic Relief Act.

Seeds of a New Acadia

In general, Acadians at the start of the 19th century had virtually no institutions of their own: the Catholic clergy came either from Québec or France, and the church was the only French institution in all the Maritimes.

There were few francophone schools and teachers, for the most part, were simple "travelling masters" who spread their knowledge from village to village. There was no French newspaper. Nor were there any lawyers or doctors. In fact, there was, as yet, no Acadian middle class. However, whether they were conscious of it or not, these Acadians sowed the seeds of a new Acadia in the soil, without any help from the state.

At the start of the 19th century, there were 4000 Acadians in Nova Scotia, 700 in Prince Edward Island, and 3800 in New Brunswick. Their establishment and growth during that century was remarkable: they counted some 87 000 at the time of Confederation and 140 000 at the turn of the century.

Growth of Collective Awareness and Identity

The Acadians began to express themselves as a people during the 1830s. They elected their first members to the legislatures of the three Maritime provinces in the 1840s and 1850s. The poem Evangeline (1847) by American author Henry W. Longfellow went through several French translations and had an undeniable impact.

In Acadia itself, a pastor born in Québec, François-Xavier Lafrance, in 1854 opened the first French-language institution of higher learning, the Séminaire Saint-Joseph, New Brunswick. It closed in 1862 but was reopened two years later by Québec priests of the congregation of the Holy Cross under the name of Collège Saint-Joseph (later amalgamated into the University of Moncton). Then, in 1867, the first French-language paper in the Maritimes, Le Moniteur Acadien, was established in Shédiac, New Brunswick. This paper was followed by L'Évangéline, the longest lasting (1887-1982), in Digby, Nova Scotia, and in 1893 by L'Impartial in Tignish, Prince Edward Island.

Religious orders of women were also coming to Acadia where they played a vital role in education and health care. The Sisters of the order of Notre Dame of Montréal opened boarding schools in Prince Edward Island at Miscouche (1864) and Tignish (1868). Also in 1868, the Sisters of Saint Joseph took charge of the lazaretto at Tracadie (now Tracadie-Sheila), New Brunswick. They also established themselves in Saint-Basile, New Brunswick, where their boarding school would eventually become Maillet College.

Just prior to Confederation, Acadians announced themselves in a spectacular way on the Maritime political scene. In New Brunswick, a majority of Acadians voted against Confederation on two different occasions. Though a large number of politicians accused them of being reactionary, it should be noted that these populations were not the only ones in the Maritimes to oppose Confederation.

The Nationalist Age (1881-1950)

As of the 1860s, an Acadian middle-class had begun to take shape. Though Saint-Joseph College and Sainte-Anne College (1890) in Church Point, Nova Scotia, definitely contributed to the emergence of an intellectual elite, there were at least four elite categories in Acadia. The two most conspicuous were the clergy and the members of the liberal professions (ie, doctors and lawyers). But even though Acadian farmers and tradesmen did not profit from the same financial resources as their English-speaking counterparts, a number of them, nonetheless, succeeded in distinguishing themselves.

As of 1881, Acadian national conventions became forums where Acadians could establish a consensus of opinion about important projects such as the promotion of agricultural development, education in French and the Acadianization of the Catholic clergy. Assemblies were held intermittently in different Acadian localities until 1930.

Acadians founded the Société Nationale de l'Acadie whose purpose was to promote the French fact. National symbols were chosen: a flag (the French tricolour with a yellow star in the blue stripe), a national holiday (the Feast of the Assumption, celebrated on August 15), a slogan ("L'union fait la force") and a national anthem (Ave Maris Stella). One of the larger victories was of Monseigneur Edouard le Blanc's appointment in 1912 as Acadia's first bishop.

Also between 1881 and 1925 at least three Acadian religious orders of women were formed. The convents run by these orders made an important contribution to improving the education of Acadian women and enhancing the cultural life of the community. These female orders also founded the first colleges for girls in Acadia, at Memramcook, New Brunswick (1913), Saint-Basile, New Brunswick (1949) and Shippagan, New Brunswick (1960).

Urbanization

The period was also characterized by an important socioeconomic turning point: the full integration of Acadians into the mainstream of Canadian industrialization and urbanization. Though the migration of Acadians to the cities was less pronounced than in other parts of Canada, a large number of them nevertheless moved to Moncton, Yarmouth and Amherst and the cities of New England to work in factories (men) and mills (women).

Certain members of the Acadian elite considered this to be a dangerous development towards assimilation into the Anglo-Saxon masses. Colonization movements from 1880 to 1940 were intended to hold back the numbers of people in exile; to divert Acadians from the largely foreign company-owned fisheries industry; and to help families fight the harsh realities of the Great Depression. The Co-Operative Movement (see alsoAntigonish Movement) in the 1930s finally allowed fishermen, after generations of exploitation, to regain control of their livelihood.

Certain distinctive regional features also emerged. Because of their larger numbers, the New Brunswick Acadians took the lead in speaking for Acadians as a whole.

Cultural Recognition

In the 1950s, Acadians started to make an impact at many levels on the economy, the politics and the culture of the Maritime Provinces. By preserving their values and culture at home, they were able to develop a French education system (mainly in New Brunswick). The vigour and distinctiveness of their culture shielded them from the devastation of assimilation and helped them to be recognized as a minority people within the Maritimes.

In terms of advantages, almost all Acadians have access to an education in French. St. Anne University in Nova Scotia and the University of Moncton in New Brunswick provide francophones with the choice of two post-secondary educational institutions offering full programs in French. The Liberal government of Premier Louis B. Robichaud made New Brunswick officially bilingual in 1969 (which does not, however, guarantee municipal services in French).

All these victories are not a guarantee of survival. The 1960s saw a sovereignty movement in Québec and an anti-bilingualism movement in the West take the stage at the national level. Ironically, as had happened in the 1750s, Acadians became caught in the middle. Nevertheless, they were able to make some gains to preserve their rights.

See also Contemporary Acadia; Culture of Acadia.

Suggested Reading

- Sheila Andrew, The Development of Elites in Acadian New Brunswick, 1861-1881 (1996); Georges Arsenault, The Island Acadians: 1720-1980 (1989); Jean Daigle, ed, Acadia of the Maritimes: Thematic Studies from the Beginning to the Present (1995); Margeurite Maillet, Histoire de la littérature acadienne: de rêve en rêve (1983); "Québec français," no 60, pp 29-50 (1985); Sally Ross and Alphonse Deveau, The Acadians of Nova Scotia: Past and Present(1992).

Acadians

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~126,146–2,000,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| 32,950 | |

| 25,400 | |

| 20,400 | |

| 11,180 | |

| 8,745 | |

| 3,020 | |

| 30,001 | |

| 815,259 | |

| 56,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Acadian French (a dialect of French with 370,000 speakers in Canada),[3] English, or both; some areas speak Chiac; those who have resettled to Quebec typically speak Quebec French. | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| French, Cajuns, French- | |

The Acadians (French: Acadiens

During the French and Indian War (the North American theater of the Seven Years' War), British colonial officers suspected Acadians were aligned with France after finding some Acadians fighting alongside French troops at Fort Beausejour. Though most Acadians remained neutral during the French and Indian War, the British, together with New England legislators and militia, carried out the Great Expulsion (Le Grand Dérangement) of the Acadians during the 1755–1764 period. They deported approximately 11,500 Acadians from the maritime region. Approximately one-third perished from disease and drowning.[7] The result was what one historian described as an ethnic cleansing of the Acadians from Maritime Canada. Other historians indicate that it was a deportation similar to other deportations of the time period.

Most Acadians were deported to various American colonies, where many were forced into servitude, or marginal lifestyles. Some Acadians were deported to England, sent to the Caribbean, and some were deported to France. After being expelled to France, many Acadians were eventually recruited by the Spanish government to migrate to present day Louisiana state (known then as Spanish colonial Luisiana), where they developed what became known as Cajun culture.[8]In time, some Acadians returned to the Maritime provinces of Canada, mainly to New Brunswick because they were barred by the British from resettling their lands and villages in what became Nova Scotia. Before the US Revolutionary War, the Crown settled New England Planters in former Acadian communities and farmland as well as, after the war, Loyalists (including nearly 3,000 Black Loyalists, who were freed slaves). British policy was to assimilate Acadians with the local populations where they resettled.[7]

Acadians speak a dialect of French called Acadian French. Many of those in the Moncton area speak Chiac and English. The Louisiana Cajundescendants speak a dialect of American English called Cajun English, with many also speaking Cajun French, a close relative of the original dialect from Canada influenced by Spanish and West African languages.

Contents

[hide]Pre-deportation history[edit]

During the seventeenth century,[when?] about sixty French families were established in Acadia. They developed friendly relations with the Wabanaki Confederacy (particularly the Mi'kmaq), learning their hunting and fishing techniques. The Acadians lived mainly in the coastal regions of the Bay of Fundy; farming land reclaimed from the sea through diking. Living in a contested borderland region between French Quebec and British territories, the Acadians often became entangled in the conflict between the powers. Over a period of seventy-four years, six wars took place in Acadia and Nova Scotia in which the Confederacy and some Acadians fought to keep the British from taking over the region (See the four French and Indian Wars as well as Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War).

While France lost political control of Acadia in 1713, the Mí'kmaq did not concede land to the British. Along with some Acadians, the Mi'kmaq from time to time used military force to resist the British. This was particularly evident in the early 1720s during Dummer's War but hostilities were brought to a close by a treaty signed in 1726.

The British Conquest of Acadia happened in 1710. Over the next forty-five years the Acadians refused to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain. Many were influenced by Father Jean-Louis Le Loutre, who from his arrival in 1738 until his capture in 1755 preached against the 'English devils'.[9] During this time period Acadians participated in various militia operations against the British and maintained vital supply lines to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour.[10] During the French and Indian War, the British sought to neutralize any military threat Acadians posed and to interrupt the vital supply lines Acadians provided to Louisbourg by deporting Acadians from Acadia.[11][12]

With the founding of Halifax in 1749 the Mi'kmaq resisted British (Protestant) settlements by making numerous raids on Halifax, Dartmouth, Lawrenc

Many Acadians might have signed an unconditional oath to the British monarchy had the circumstances been better, while other Acadians did not sign because they were clearly anti-British.[14] For the Acadians who might have signed an unconditional oath, there were numerous reasons why they did not. The difficulty was partly religious, in that the British monarch was the head of the (Protestant) Church of England. Another significant issue was that an oath might commit male Acadians to fight against France during wartime. A related concern was whether their Mi'kmaq neighbours might perceive this as acknowledging the British claim to Acadia rather than the Mi'kmaq. As a result, signing an unconditional oath might have put Acadian villages in dangers of attack from Mi'kmaq.[15]

Deportation[edit]

In the Great Expulsion (le Grand Dérangement), after the Battle of Fort Beauséjour beginning in August 1755 under Lieutenant Governor Lawrence, approximately 11,500 Acadians (three-quarters of the Acadian population in Nova Scotia) were expelled, their lands and property confiscated, and in some cases their homes burned. The Acadians were deported throughout the British eastern seaboard colonies from New England to Georgia. Although measures were taken during the embarkation of the Acadians to the transport ship, some families became split up. After 1758, thousands were transported to France. Most of the Acadians who went to Louisiana were transported there from France on five Spanish ships provided by the Spanish Crown to populate their Louisiana colony and provide farmers to supply New Orleans. The Spanish had hired agents to seek out the dispossessed Acadians in Brittany and the effort was kept secret so as not to anger the French King. These new arrivals from France joined the earlier wave expelled from Acadia, creating the Cajun population and culture.

The Spanish forced the Acadians they had transported to settle along the Mississippi River, to block British expansion, rather than Western Louisiana where many of them had family and friends and where it was much easier to farm. Rebels among them marched to New Orleans and ousted the Spanish governor. The Spanish later sent infantry from other colonies to put down the rebellion and execute the leaders. After the rebellion in December 1769 the Spanish Governor O'Reilly permitted the Acadians who had settled across the river from Natchez to resettle on the Iberville or Amite river closer to New Orleans.[16]

A second and smaller expulsion occurred when the British took control of the North Shore of what is now New Brunswick. After the fall of Quebec the British lost interest and many Acadians returned to British North America, settling in coastal villages not occupied by American colonists. A few of these had evaded the British for several years but the brutal winter weather eventually forced them to surrender. Some returnees settled in the region of Fort Sainte-Anne, now Fredericton, but were later displaced by the arrival of the United Empire Loyalists after the American Revolution.

In 2003, at the request of Acadian representatives, Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada issued a Royal Proclamation acknowledging the deportation and establishing July 28 as an annual day of commemoration, beginning in 2005. The day is called the "Great Upheaval" on some English-language calendars.

Geography[edit]

The Acadians today live predominantly in the Canadian Maritime provinces, as well as parts of Quebec, Louisiana and Maine. In New Brunswick, Acadians inhabit the northern and eastern shores of New Brunswick, from Miscou Island (French: Île Miscou) Île Lamèque including Caraquet in the center, all the way to Neguac in the southern part, Grande-Anse in the eastern part and Campbellton through to Saint-Quentin in the northern part. Other groups of Acadians can be found in the Magdalen Islands and throughout other parts of Quebec. Many Acadians still live in and around the area of Madawaska, Maine where the Acadians first landed and settled in what is now known as the St. John Valley. There are also Acadians in Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia such as Chéticamp, Isle Madame, and Clare. East and West Pubnico, located at the end of the province, are the oldest regions still Acadian.

The Acadians settled on the land before the deportation and returned to some of the same exact land after the deportation. Still others can be found in the southern and western regions of New Brunswick, Western Newfoundland and in New England. Many of these latter communities have faced varying degrees of assimilation. For many families in predominantly Anglophone

The Acadians who settled in Louisiana after 1764, known as Cajuns, have had a dominant cultural influence in many parishes, particularly in the southwestern area of the state known as Acadiana.

Culture[edit]

Today Acadians are a vibrant minority, particularly in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Louisiana (Cajuns), and northern Maine. Since 1994, Le Congrès Mondial Acadien has united Acadians of the Maritimes, New England, and Louisiana.

August 15, the feast of the Assumption, was adopted as the national feast day of the Acadians at the First Acadian National Convention, held in Memramcook, New Brunswick in 1881. On that day, the Acadians celebrate by having the tintamarre which consists mainly of a big parade where people can dress up with the colours of Acadia and make a lot of noise.

The national anthem of the Acadians is "Ave, maris stella", adopted at Miscouche, Prince Edward Island in 1884. The anthem was revised at the 1992 meeting of the Société Nationale de l'Acadie, where the second, third and fourth verses were changed to French, with the first and last kept in the original Latin.

The Federation des Associations de Familles Acadiennes of New Brunswick and the Société Saint-Thomas d'Aquin of Prince Edward Island has resolved that December 13 each year shall be commemorated as "Acadian Remembrance Day" to commemorate the sinking of the Duke Williamand the nearly 2000 Acadians deported from Ile-Saint Jean who perished in the North Atlantic from hunger, disease and drowning in 1758.[17]The event has been commemorated annually since 2004 and participants mark the event by wearing a black star.

Today, there are cartoons featuring Acadian characters and an Acadian show named Acadieman.

Artistic commemorations of The Expulsion[edit]

In 1847, American writer Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published Evangelin

In the early 20th century, two statues were made of Evangeline, one in St. Martinville, Louisiana and the other in Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia, which both commemorate the Expulsion. Robbie Robertson wrote a popular song based on the Acadian Expulsion titled Acadian Driftwood, which appeared on The Band's 1975 album, Northern Lights – Southern Cross.

Antonine Maillet's Pélagie-la-charette

The Acadian Memorial (Monument Acadien)[18] honors those 3,000 who settled in Louisiana.

Throughout the Canadian Maritime Provinces there are Acadian Monuments to the Expulsion, such as the one at Georges Island (Nova Scotia) and Beaubears Island.

Flags[edit]

The flag of the Acadians is the French tricolour with a golden star in the blue field (see above), which symbolizes the Saint Mary, Our Lady of the Assumption, patron saint of the Acadians and the "Star of the Sea". This flag was adopted in 1884 at the Second Acadian National Convention, held in Miscouche, Prince Edward Island.

Acadians in the diaspora have adopted other symbols. The flag of Acadians in Louisiana, known as Cajuns, was designed by Thomas J. Arceneaux of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, and adopted by the Louisiana legislature as the official emblem of the Acadiana region in 1974.[19]

A group of New England Acadians attending Le Congrès Mondial Acadien in Nova Scotia in 2004, endorsed a design for a New England Acadian flag[20] by William Cork, and are advocating for its wider acceptance.

Prominent Acadians[edit]

Notable Acadians in the 18th century include Noel Doiron (1684–1758). Noel was one of more than 350 Acadians that perished on the Duke William on December 13, 1758.[21] Noel was described by the Captain of the Duke William as the "father of the whole island", a reference to Noel's place of prominence among the Acadian residents of Isle St. Jean (Prince Edward Island).[22] For his "noble resignation" and self-sacrifice aboard the Duke William, Noel was celebrated in popular print throughout the 19th century in England and America.[23][24][25] Noel also is the namesake of the village Noel, Nova Scotia.

Another prominent Acadian from the 18th century was militia leader Joseph Broussard who joined French priest Jean-Louis Le Loutre in resisting the British occupation of Acadia.

More recent notable Acadians include singers Angèle Arsenault and Edith Butler, singer Jean-François Breau, writer Antonine Maillet; film director Phil Comeau; singer-songwriter Julie Doiron; artist Phoebe Legere, boxers Yvon Durelle and Jacques LeBlanc; pitcher Rheal Cormier; former Governor General Roméo LeBlanc; former premier of Prince Edward Island Aubin-Edmond Arsenault, the first Acadian premier of any province and the first Acadian appointed to a provincial supreme court; Aubin-Edmond Arsenault's father, Joseph-Octave Arsenault, the first Acadian appointed to the Canadian Senate from Prince Edward Island; Peter John Veniot, first Acadian Premier of New Brunswick; and former New Brunswick premier Louis Robichaud, who was responsible for modernizing education and the government of New Brunswick in the mid-20th century.

Prominent Louisiana Acadians include Senator Dudley J. LeBlanc, Singer-Songwriter Zachary Richard, Attorney-cultural activist Warren Perrin, and historian and President of the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL) William Arceneaux.

See also[edit]

- List of Acadians

- History of Nova Scotia

- Military history of Nova Scotia

- Military history of the Acadians

- Acadian cuisine

- Lee Roy J. Pitre, Jr., Author, Software Engineer Pitre *Pitres.us *His

tory & Origin of Pitre "Acadians/Cajuns"

Notes[edit]

- ^ For information on Acadians who also have Indigenous ancestry, see:

- Parmenter, John; Robison, Mark Power (April 2007). "The Perils and Possibilities of Wartime Neutrality on the Edges of Empire: Iroquois and Acadians between the French and British in North America, 1744–1760". Diplomatic History. 31 (2): 182. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.

2007.00611.x. - Faragher (2005), pp. 35-48, 146-67, 179-81, 203, 271-77

- Paul, Daniel N. (2006). We Were Not the Savages: Collision Between European and Native American Civilizations. Fernwood. pp. 38–67, 86, 97–104. ISBN 978-1-55266-209-0

. - Plank, Geoffrey (2004). An Unsettled Conquest: The British Campaign Against the Peoples of Acadia. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 23–39, 70–98, 111–14, 122–38. ISBN 0-8122-1869-8.

- Robison, Mark Power (2000). Maritime frontiers: The evolution of empire in Nova Scotia, 1713-1758 (PhD). University of Colorado at Boulder. pp. 53–84.

- Wicken, Bill (Autumn 1995). "26 August 1726: A Case Study in Mi’kmaq-New England Relationships in the Early 18th Century". Acadiensis. XXIII (1): 20–21.

- Wicken, William C. (1998). "Re-examining Mi’kmaq-Acadian Relations, 1635-1755". In Dépatie, Sylvie; Desbarats, Catherine. Vingt ans apres, Habitants et marchands: Lectures de l'histoire des XVIIe et XVIIIe siecles canadiens. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 93–109. ISBN 978-0-7735-

6702-3. - Morris, Charles. A Brief Survey of Nova Scotia. Woolwich: The Royal Artillery Regimental Library.

The people are tall and well proportioned, they delight much in wearing long hair, they are of dark complexion, in general, and somewhat of the mixture of Indians; but there are some of a light complexion. They retain the language and customs of their neighbours the French, with a mixed affectation of the native Indians, and imitate them in their haunting and wild tones in their merriment; they are naturally full cheer and merry, subtle, speak and promise fair,...

- Bell, Winthrop Pickard (1961). The Foreign Protestants and the Settlement of Nova Scotia: The History of a Piece of Arrested British Colonial Policy in the Eighteenth Century. University of Toronto Press. p. 405.

Many of the Acadians and Mi'kmaq people were mixed bloods , foreign aboriginals or métis example, when Shirley put a bounty on the Mi'kmaq people during King George's War, the Acadians appealed in anxiety to Mascarene because of the "great number of Mulattoes amongst them".

- Parmenter, John; Robison, Mark Power (April 2007). "The Perils and Possibilities of Wartime Neutrality on the Edges of Empire: Iroquois and Acadians between the French and British in North America, 1744–1760". Diplomatic History. 31 (2): 182. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.

References[edit]

- ^ "Canadian census, ethnic data". Retrieved 18 March 2013.

A note on interpretation: With regard to census data, rather than going by ethnic identification, some would define an Acadian as a native French-speaking person living in the Maritime provinces of Canada. According to the same 2006 census, the population was 25,400 in New Brunswick; 34,025 in Nova Scotia; 32,950 in Quebec; and 5,665 in 03-18

- ^ "Detailed Mother Tongue, Canada– Île-du-Prince-Édouard". Archived from the original on July 25, 2009.

- ^ "File not found - Fichier non trouvé". statcan.ca. Retrieved 2 April2016.

- ^ Pritchard, James (2004). In Search of Empire: The French in the Americas, 1670-1730. Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-521-82742-3.

Abbé Pierre Maillard claimed that racial intermixing had proceeded so far by 1753 that in fifty years it would be impossible to distinguish Amerindian from French in Acadia.

- ^ Landry, Nicolas; Lang, Nicole (2001). Histoire de l'Acadie. Les éditions du Septentrion. ISBN 978-2-89448-

177-6. - ^ Griffiths, N.E.S. (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-7735-2699-0.

- ^ a b Lockerby, Earle (Spring 1998). "The Deportation of the Acadians from Ile St.-Jean, 1758". Acadiensis. XXVII (2): 45–94. JSTOR 30303223.

- ^ Han, Eunjung; Carbonetto, Peter; Curtis, Ross E.; Wang, Yong; Granka, Julie M.; Byrnes, Jake; Noto, Keith; Kermany, Amir R.; Myres, Natalie M. (2017-02-07). "Clustering of 770,000 genomes reveals post-colonial population structure of North America". Nature Communications. 8. ISSN 2041-

1723. doi:10.1038/ncomms14238. - ^ Parkman, Francis (1914) [1884]. Montcalm and Wolfe. France and England in North America. Little, Brown.

- ^ Grenier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710–1760. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-8566-8.

- ^ Patterson, Stephen E. (1998). "Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749–61: A Study in Political Interaction". In Buckner, Phillip Alfred; Campbell, Gail Grace; Frank, David. The Acadiensis Reader: Atlantic Canada Before Confederation. pp. 105–106.

- ^ Patterson, Stephen. Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-919107-44-1

. - ^ Faragher (2005), pp. 110–112.

- ^ For the best account of Acadian armed resistance to the British, see Grenier, John. The Far Reaches of Empire. War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 2008.

- ^ Reid, John G. (2009). Nova Scotia: A Pocket History. Fernwood. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-55266-325-7.

- ^ Holmes, Jack D.L. (1970). A Guide to Spanish Louisiana, 1762-1806. A. F. Laborde. p. 5.

- ^ Pioneer Journal, Summerside, Prince Edward Island, 9 December 2009.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Acadian Memorial - The Eternal Flame". Retrieved October 18,2012.

- ^ "Acadian Flag". Acadian-Cajun.com. Retrieved 2011-10-02.

- ^ "A New England Acadian Flag". Archived from the original on 2011-09-07. Retrieved 2011-10-02.

- ^ Scott, Shawn; Scott, Tod (2008). "Noel Doiron and East Hants Acadians". The Journal of Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society. 11: 45.

- ^ Journal of William Nichols, "The Naval Chronicle", 1807.

- ^ Frost, John (1846). The Book of Good Examples; Drawn From Authentic History and Biography. New York: D. Appleton & Co. p. 46.

- ^ Reubens Percy, "Percey's Anecdotes", New York: 1843, p. 47

- ^ "The Saturday Magazine", New York: 1826, p. 502.

References[edit]

- Dupont, Jean-Claude (1977). Héritage d'Acadie (in French). Montreal: Éditions Leméac.

- Faragher, John Mack (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from Their American Homeland. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-24243-0

. - Frink, Tim (1999). New Brunswick, A Short History (2nd ed.). Summerville, New Brunswick: Stonington Books. ISBN 978-0-9682-5001-3.

- Scott, Michaud. "History of the Madawaska Acadians". Retrieved 2008-03-05..

- Mosher, Howard Frank (1997). North Country: A Personal Journey Through the Borderland. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-

39124-6.

Further reading[edit]

- Chetro-Szivos, J. Talking Acadian: Work, Communication, and Culture, YBK 2006, New York ISBN 0-9764359-6-9.

- Griffiths, Naomi. From Migrant to Acadian: a North American border people, 1604–1755, Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2005.

- Hodson, Christopher. The Acadian Diaspora: An Eighteenth-Century History (Oxford University Press; 2012) 260 pages online review by Kenneth Banks

- Jobb, Dean. The Acadians: A People's Story of Exile and Triumph, John Wiley & Sons, 2005 (published in the United States as The Cajuns: A People's Story of Exile and Triumph)

- Kennedy, Gregory M.W. Something of a Peasant Paradise? Comparing Rural Societies in Acadie and the Loudunais, 1604-1755 (MQUP 2014)

- Laxer, James. The Acadians: In Search of a Homeland, Doubleday Canada, October 2006 ISBN 0-385-66108-8.

- Le Bouthillier, Claude, Phantom Ship, XYZ editors, 1994, ISBN 978-1-894852-09-8

- Magord, André, The Quest for Autonomy in Acadia (Bruxelles etc., Peter Lang, 2008) (Études Canadiennes - Canadian Studies, 18).

- Naomi E. S. Griffiths, The Acadian Deportation: Deliberate Perfidy or Cruel Necessity? Toronto: Copp Clark, 1969.

- Runte, Hans R. (1997). Writing Acadia: The Emergence of Acadian Literature 1970–1990. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-0237-1

.

External links[edit]

- 1755: The History and the Stories

- Acadian-Cajun History & Genealogy – Acadian-Cajun culture, history, & genealogy.

- Acadian.org - Oldest Acadian history and genealogy website

- Musee acadien and Research Centre of West Pubnico

- Jean Pitre circa 1635

- Acadians of Madawaska, Maine

- Quit rents paid by Acadians (1743-53)

Comments

Post a Comment